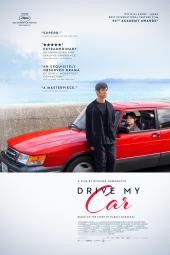

Drive My Car (2021)

Directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Written by Ryusuke Hamaguchi and Takamasa Oe

Starring Hidetoshi Nishijima, Toko Miura, Masaki Okada, Reika Kirishima, and Peri Dizon

179 minutes, Unrated

Drive My Car is a film that was released in 2021. I didn’t see it until 2022. As I sat through the closing credits and pondered the immensely powerful cinematic treasure I had just seen, I wished that this film would have been available to me in 2002. I could have used this movie back then.

If you are unaware of this film, then you must not be the sort that pays attention to the Academy Awards, because Drive My Car has been recently nominated for four Oscars. A three-hour subtitled foreign film, it is the official submission of Japan in the Best International Feature Film category, but it has also achieved nods for Best Director (Ryusuke Hamaguchi) and Best Picture. The screenplay, adapted by the director and Takamasa Oe from a short story by Hiruki Murakami (one of my favorite living novelists), has been honored in the category of Best Adapted Screenplay.

If you are aware of this film, but have not seen it, I caution you from moving forward until you have. This entry will contain many, many SPOILERS. Ordinarily, I would not spoil a movie this new, but I simply cannot write about why this film has spoken to me so profoundly without divulging plot details. This is, to me, a very special film.

Drive My Car follows famed actor and director Yusuke (played by Hidetoshi Nishijima) as he directs a multilingual production of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya in Hiroshima. The agreement to entrench himself so deeply in an emotional theatrical production is clearly an attempt to distract himself from dealing with the grief over the recent death of his wife, Oto (played by Reika Kirishima). This plot is cushioned by subplots that involve his intentional casting of his deceased spouse’s former lover (played by Mosaki Okada) in the lead role of his play and his frustration that his employers are requiring him to be chauffered around by a quiet and reserved woman named Misaki (played by Tiko Miura). For the most part, the narrative is somewhat plotless and meandering– there are extended sequences of just two people talking in a car, scenes that depict the sometimes tedious process of mounting a theatrical endeavor– but that doesn’t prevent the story from delivering an emotional gut punch by the end. This is a film about grief, how we process it, and how we occupy ourselves when we cannot. There are no car chases or gunfights. There are no explosions or fisticuffs. There are only real people here who serve to remind us that we do not have to be defined forever by the terrible things that happen to us.

Early in the film, I had a suspicion that this particular narrative might be offering truths that I was ill-equipped to handle emotionally and psychologically. Before the opening credits have even rolled, Yusuke has entered his apartment to discover his wife engaged in sexual congress with another man. He doesn’t even react. He doesn’t speak or somehow make his presence at this moment of intimacy known. He just quietly turns and exits the apartment.

This sequence unsettled me, gave me pause, because this very thing had happened to me in real life. I didn’t walk in on it, but I could hear them. I had been standing in the foyer outside her apartment door, fist poised to knock, when I hesitated because I could clearly hear her on the other side of the door– more than likely on the couch right next to the entry– having sex with someone who was not me. I just left. I never mentioned it. I did, however, end the relationship a few days later. There were plenty of reasons that we should not remain together without having to go through the embarrassment and rejection of admitting that I knew I had been cuckolded.

Reservations about the memories Drive My Car might eventually dredge up aside, I continued watching the film. I was conflicted because I really liked Yusuke’s wife, despite knowing everything that the film had so-far revealed about her, and I really liked the two of them together. Soon, though, she dies from a brain aneurysm and my distaste for her actions was replaced with a deep sorrow for Yusuke. I had begun to relate to Yusuke in ways, and for reasons, that I was only slowly beginning to process as I watched the film.

The entire movie was a bit of an emotional rollercoaster for me because I saw so much of myself in Yusuke. In many ways, it seemed to me that Yusuke and I might be one in the same, as if this script was an adaptation of my own exploits and travails. Every scene seemed to be throwing something else that I had been through in my life right into plain view for an audience to witness. I, too, had been unable to finish a performance because the words I was reciting were, in the moment, too much for me to deal with (Marks of the Devil, 2000). I had, just a couple of years ago, been forced to replace my lead actor in a psychologically-challenging and verbally-difficult role mere days before the curtain was to rise (No Exit, 2019). Once, I sat– in the backseat of a car, no less– with the man Sara had cheated on me with and listened to his story, which revealed, without it ever being explicitly stated, that there were aspects of her being and personality that I was never going to be privy to no matter how hard I tried. The only real difference between Yusuke and myself is how stoic and calm he always remained. I have never been very good at calm. In fact, my own inability to remain relaxed under pressure, my burning powder keg of a volatile temper, got me arrested in 2002. This arrest happened at the theatre, on stage in front of cast, crew, and audience, while I was performing, another event in my life that I saw mirrored in this film, although, in this instance, it was a character besides Yusuke that faces those repercussions.

Yes, this movie kicked me hard, repeatedly, after it had already knocked me down. It forced me to stand toe-to-toe with things that I had intentionally not allowed myself to remember or think about. I felt, in some ways, though, that I had found a new soulmate in Yusuke, and I wished that he were real, and that he and I were friends, and that he could have mentored me on existential-crisis resolution back in 2002, the precise year that I began to allow my personal demons to let everything important to me turn to shit. I was numb by the time the movie had ended, unable to rise from my seat as the ending credits scrolled in front of me. Fifteen years ago, this movie would have probably sent me to the nearest bar for the tallest and strongest glass of gin they could legally sell me, but I’m stronger than that now, so instead I wandered the shopping district of Normal, Illinois and bought comic books, a Human Torch action figure, and a paperback copy of Commonwealth. I reflected strongly on the film that I had just seen, but, removed from it if even for just an hour, I was less defeated by its contents now and more emboldened by the message that Drive My Car seemed to be conveying. That message: You are more than the terrible things that have happened to you. Define those things, and deal with them, before they begin to define and deal with you.

I spent many years of my life allowing the bad things that happened to me be the explanation for my own erratic behavior. Yes, a woman I loved deeply cheated on me for the worst possible reasons, but I used that as an excuse to self-destruct. I lost myself in drugs and alcohol, but justified it as it seemed to be fueling a prolific stream of creativity for which I was proud to be associated. Years later, I wanted to blame Liz’s insecurity and neuroses for my plummet to rock bottom, but the seeds for that fall from grace had already been planted. She might have watered them, but I had buried them. By then, the world at large had become less intrigued by my creative energy, seeing it as a front to camouflage my rotten temperament, increasing inconsistency, and now-notorious unreliability. For a goodly while, what Sara had done to me defined me. The urge to separate myself from it, the need to prove that I was beyond it, even when I hadn’t properly dealt with it, only led to that definition being eventually rewritten so that now I was being defined by what I had done to Liz. If I could have just let my time with Sara be “something that has happened to me”, I’d have saved myself a lot of grief. There are other events along the way that I probably, in retrospect– hindsight being what it is– should have labelled in such a fashion, but Sara was the first. She was the springboard.

On the way home from my excursion to the Normal Theatre, I called my wife. Naturally, I talked about this movie and how powerful I thought it was. My wife, who has little interest in any movie that doesn’t star Vin Diesel or have the words “fast” or “furious” in the title, said that this movie sounded depressing. I agreed that it was. At least, it was in the moment, but was it really? Isn’t there something very uplifting in the knowledge that you have always been capable of unpacking something horrible just long enough to fold it back up, stow it away, and say “You no longer have power over me”? I find it refreshing that profound pathos is a gateway drug to profound catharsis. For me, Drive My Car was nothing but cathartic.

As I completed my hour-long drive home from the theatre (Drive My Car was not playing anywhere locally), I had a fascinating conversation with myself. I realized that the events of late 1998 to late 2000– my time with Sara– had actually become “something that has happened to me” long before I was ready to admit it. I write about her, and that era, often and there’s a sense of detachment to it. It could be argued that said detachment makes heartbreaking things easier to write about, but I have to concede that I have a slew of other heartbreaking things that I haven’t been able to write about. Things I’m not proud of. Things I haven’t properly dealt with. Things I’m not ready to properly deal with. I’ve mentioned already that Sara was a springboard, and she was, but she provided that service in more ways than one. My reaction to her, my self-destructive inability to appropriately respond to what we went through, led to everything that eventually culminated in the decision to seek assistance with my mental health in 2006. I sought sobriety and therapy, two key elements in my toolbox of repair. I’m a better person for it, more content and self aware. Those two things are key elements in my toolbox of happiness. Without them, I wouldn’t have my wife, or my beautiful twin boys, or the ability to not pummel the life out of the nearest wall when the best-laid plans go south.

I’ll be honest and admit that I hadn’t really connected Drive My Car to Sara for most of the duration of the screening. My first connection to her was actually very pleasant, an image in the movie that reminded me of one of my fondest memories of her. In 1998– we had not been dating long– I went to Charleston, West Virginia to spend Christmas with her. This was a decision of considerable controversy to my family since Michelle and I had only been separated a few months, but I was not willing to deal with the questions about the demise of my marriage that would surely pervade the holiday celebrations if I were to stay home. Sara’s parents were not completely comfortable with me, however, so Sara and I spent a lot of time doing things outside of her parent’s house. When I got to Charleston, I could not secure a rental car right away, so, for that first night, we were at the mercy of her mother and father and their car. There was one rule about the car: no smoking cigarettes in the car.

That night, Sara and I drove around Charleston as she gave me a guided tour of her stomping grounds. The capitol building was all lit up and decorated for Christmas, and she wanted me to see it, so we drove out to the center of town. We parked her parent’s Audi in the parking lot and talked for a while by the light of the colorful display. At a certain point, Sara realized that the lights seemed to be changing– blinking on, off, rearranging– in a particular pattern. I mean, it was obvious from the get-go that the lights were changing, but Sara– an incredibly talented musician– was detecting a rhythm that did not seem random. It got very quiet as she studied the rhythmic changing of the multi-colored bulbs. She was studying it, trying to see if the rhythm alone was discernible as a recognizable pattern– a Christmas carol, perhaps. We sat there a long time before she eventually figured it out. It was “Oh, Holy Night”. Almost as soon as she deciphered it, though, the pattern changed again, so we waited a while longer to figure out the next song, but this new carol was a mystery to us and she never decoded it (We would later discover that the lights were, in fact, timed to a setlist of carols, and there was a radio station that you could tune to for following along). It was decided that we should head back home before her parents became concerned that we were copulating in a coal mine, but we wanted a cigarette first and there was absolutely NO SMOKING IN THE CAR! It was also about seven degrees outside, though, so Sara popped open the sunroof and we sat in the warmth of the vehicle with our cigarettes sticking up through the opening. When we took a drag, we popped our heads out like Whack-A-Mole. The smoke from our cigarettes and from our exhalations dissipates into the Charleston air. We smoked about four cigarettes apiece like that before she kissed me long and deep by the syncopated lights of “Do You Hear What I Hear?” and then we drove home. I have never let go of that memory, and if you have seen Drive My Car, you will know why it came to mind.

When this blast from my past happened in the film, I had a moment of relief. Here, at last, was something in Drive My Car that had happened to me that wasn’t cringe-inducing and uncomfortable. I was overcome by a fond nostalgia that lasted until Koji sits in the back of the car and tells Yusuke about the final scenes of Oto’s unfinished screenplay, the final proof that Yusuke needs that Koji had been the lover he walked in on, and then fond nostalgia became uncomfortable anger again as I remembered Eric in the backseat of a taxicab, drunkenly crying about abortions and sex with an unnamed woman that sounded way too much like my girlfriend.

That’s the thing about nostalgia: it can turn on you. For every memory of smoking cigarettes through the sunroof of an Audi, there’s an argument about missing CDs that were stolen and sold for cigarette money. For every pleasant recall of slow dancing in the kitchen to Dave Matthews Band at 3:00 am to the light of an open refrigerator door, there’s an argument about where she’s been, who she’s been with, and what she was doing while there. Every “I love you” ever uttered is magically erased by “You’re evil”, which is what I said– “You’re fucking evil!”– when it became clear exactly what she had done. Nostalgia is like that German Shepherd Gary Sinise references in The Green Mile: friendly enough until it attacks you over a bag of hamburgers. That is precisely, I think, why it’s a good idea to learn how to let the troublesome events of your past become “something that happened to you.”

Of the many things that I felt after my initial viewing of Drive My Car that is perhaps the most personally important: You should not be defined by your grief. Believe me when I say that I have thought about this movie a lot since seeing it, and I keep coming back to that. Own your grief, but don’t let it be your description. We should be defined by what we have learned from our struggles, how we move on from them, and how we resolve to do better in the future. It’s not easy. Trust me when I tell you that.